What is the potential for solar lanterns to improve education outcomes in rural off-grid regions? This is a question a new study in the Zimba district of Zambia looked to answer.

The study results from collaboration between SolarAid, Acumen and Stanford University with funding from the Stanford Institute for Innovation in Developing Economies. The research included over 1,400 students in grades 7 to 9 – the last three classes of primary school – attending 12 government schools in the Zimba district of Zambia.

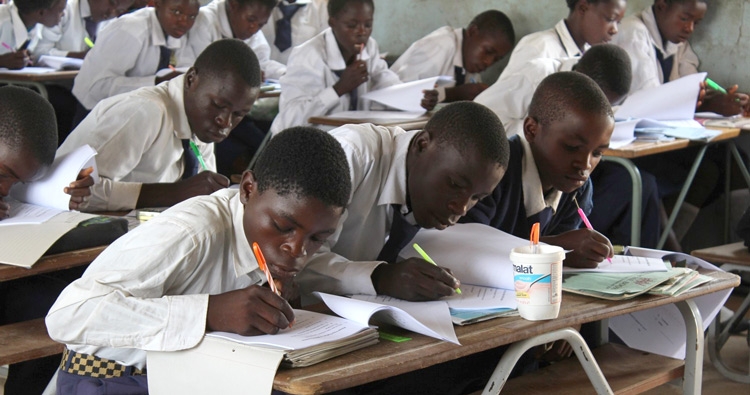

Students studying in Zambia – photo credit Kat Harrison

The solar lights were disseminated for free in a ‘blind’ randomised control trial (RCT) where students won different prizes in a raffle – for example, a school bag or soap. This was to keep the data, collected through interviews with the students, as impartial as possible – the students did not know the researchers were looking for results specifically on the solar light.

As so many variable impact educational outcomes, the study explored financial poverty as a limiting factor for educational opportunity for many reasons. For example, the research shows that many children have extremely busy days, with their time and energy taken up with helping out in the home and, often, the need to earn money. This really underlines the challenging environments in which hundreds of millions of people are living across rural sub-Saharan Africa, where poverty limits opportunity.

While the study was unable to detect widespread educational impacts of solar lanterns, one possible reason being the low use of the lanterns (15%) used in the research group, it did establish that a significant number of off grid households in the Zimba district of Zambia are using battery powered torches. This is interesting and certainly matches our observations in the marketplace where there is an ever increasing array of battery powered torches and lanterns available. SolarAid research with the public and solar light customers tells us a common source of off-grid lighting for families is torches, not kerosene lanterns as in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania.

We take the view that the battery powered torches on the market are, from a health and safety perspective, better options than candles and kerosene lanterns and it is good to see the decline of these fossil fuels being used for lighting in Zimba. The quality and lifespan of many of these lights is less clear, however. It is also important to consider that they do require people to repeatedly purchase batteries, the cheapest of which last just a matter of days. This results in the challenge of how to safely dispose of them in an environmentally friendly way in rural areas with limited infrastructure. The fact that SolarAid has sold many solar lights in Zambia demonstrates the added value that these little lights can bring over torches.

What the research does not tell us, is why many of the solar lights distributed as part of the study remained unused. Possible reasons include the reported problems experienced with the switches on many of the lights, other members of families using the solar light or maybe the children preferring to use a torch already purchased by the family.

It could be, however, because there was less social marketing around the potential role the solar lights can play. When the children received their free solar light in this study, they were given an information card which “emphasized that the lantern could be helpful for studying.” They were also shown how to use the solar light by research staff who repeated the message.

While this bares similarities to SolarAid’s School Campaign, we work through local head teachers, trusted members of their communities, to emphasise the studying potential of a solar light to students and also the parents of students. The head teachers and schools themselves are the ‘agents of change’ rather than research staff.

This may affect the motivation for purchase and subsequent usage in the household. Through this model, teachers across five countries have told us about the benefits.

For example, head teachers like Mr Hachilangu in Zambia and Mr. Mkhwichi in Malawi inspire and motivate students and the parents of students to use solar lights for studying. Mr Hachilangu tells us this has led to better grades and Mr Mkhwichi proudly explains how solar lights have helped the first students ever from his school graduate to secondary school. This was in his letter to us entitled, ‘An amazing report on the wonderful success of SunnyMoney project at Koche School.’

While different to evidence we have had before, the results of this study are not too surprising when considering the context. It is entirely possible the impact would have been more significant if the baseline use of lighting was not torch light, but kerosene or candles. There is certainly more we need to understand about this form of energy and the perception of it.

Furthermore, why was the usage of the solar lights low? Would it have been higher if our School Campaign model was used instead, or if we had replaced the lights sooner? These are useful questions for us to explore in continuing to evolve our model and service to our customers.

We are confident that in any context, the overall impact of a solar light is more significant than torch lighting. The questions posed by this study are the first steps to understanding more and how we can use them to reach millions more families with clean and affordable energy.

If you’d like to read more about the results of this research, please see the full academic working paper Assessing Opportunities for Solar Lanterns to Improve Educational Outcomes in Rural OffGrid Regions: Challenges and Lessons from a Randomized Controlled Trial.