Anger boiled over after a national blackout, which saw babies dying in incubators, yet outages are frequent—for the lucky 10 percent of people with electricity in Malawi.

Rural health worker Patrick Kamzitu is relaxed about the long and frequent power cuts that plague Malawi and which recently almost brought it to a halt when the whole country went dark for two hours.

Power cuts? We have no power cuts here. We hear of what is happening in the cities but we have no problem here because we don’t have any electricity to cut,

Nambuma, a small town 50 kilometres over dirt tracks north-west of the capital Lilongwe, was promised mains power by the government five years ago. But although there are new poles lying on the side of the road five miles away in Ngoni, the electricity has still not come.

Like almost 90 percent of Malawians, the 12 000 people living in the Nambuma area are resigned to never being able to switch on the lights. But patience is wearing thin for the 10 percent of Malawian households that are connected to the grid and are supplied by the State-owned Electricity Supply Corporation of Malawi, Escom.

Prices have risen sharply, and daily rationing and lengthy “outages” lasting from a few hours to 25 hours, depending on where people live, are now the norm. A familiar sound in Lilongwe, Blantyre and Mzuzu, the country’s three urban centres, is of diesel generators kicking in as the lights flicker and go out.

People are long used to shrugging and accepting the cuts, but anger boiled over during the two-hour national blackout. Irate members of Parliament—who were meeting at the time at Parliament Building in Lilongwe—were forced to use their mobile phones to read in Parliament businesses. They complained about having to burn expensive diesel and there were threats of demonstrations.

Escom was forced to make a rare public apology, blaming the national blackout on a fault on the power line between two of the country’s largest hydroelectric plants.

There are people’s lives concerned here. We have cases of premature babies dying in hospitals due to the absence of power for the incubators. This is unacceptable.

Says Dorothy Ngoma, president of the National Organisation of Nurses and Midwives of Malawi.

The usual explanation for power cuts in December is that it’s the end of the dry season, when water levels in Lake Malawi and the Shire river, which together feed the country’s largest hydroelectricity plants, are at their lowest. In the past three weeks hydroelectric output has been halved, a figure worsened by the two-year drought brought on by El Niño, which has left lake levels at historically low levels.

New back-up diesel generators, hydro and solar plants are due to be installed shortly which should improve the situation in 2018, say the power companies, but they warn that people must be patient.

But it will be decades before every household gets connected.

Malawi has the capacity to generate just 351 megawatts (MW), which is little more than a single Scottish wind farm; and even without a creaking infrastructure its power companies cannot keep up with soaring demand from a fast growing population and fuel-hungry companies needing electricity for computers and manufacturing.

The country faces a widening gap between electricity demand and supply, which is being exacerbated by urbanisation, economic development and population growth,

says John Taulo, deputy director of the Malawi Industrial Research and Technology Development Centre in Blantyre.

Grid coverage is growing slowly but demand is doubling every 10 years or so. We are faced with serious energy supply problems, including rising energy and electricity demand; insufficient power generation capacity; increasingly high oil import bills; lack of investment in new power generation units; high transmission and distribution costs, transmission losses; poor power quality and reliability

he says.

No electricity, no development

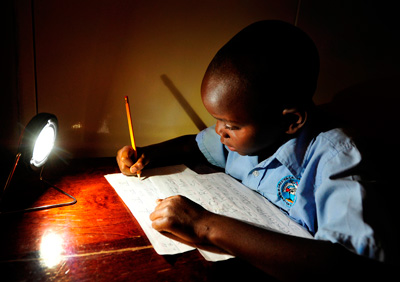

A child studies by solar lamp (photo by Patrick Bentley)

No electricity means no development but also widespread environmental degradation, according to the United Nations Development Programme.

Nearly 75 percent of Malawian households depend on charcoal and wood burning for cooking, and coal and fossil fuel imports have grown, it says. Charcoal production is now big business, with people carrying it many miles to sell in cities.

Aside from the indoor health impact of burning wood to cook, deforestation also leads to soil erosion, which, in a vicious circle, silts up the rivers and blocks the hydroelectricity plants.

The power cuts keep the country poor and hungry, says the World Bank, which calculates that electricity rationing loses Malawi up to 7 percent of its GDP a year. This is more than any other country in Africa. In comparison, Kenya, Niger, Madagascar and Benin all lose under 2 percent.

There is a strong link between human development and per capita electricity consumption, say researchers.

Malawi has one of the world’s lowest electricity consumption levels and its human development index, of 0.418, is far below even the sub-Saharan regional average, ranking 170 out of 187 countries in the world.

Massive investment is needed if it and many other sub-Saharan African countries are to generate electricity and meet their development goals, says Mac Cosgrove-Davies, the World Bank’s global lead for energy access.

At a December meeting in Abuja, Nigeria he said:

One billion people have no access to electricity, and six out of 10 of them, or 600 million people, are in Africa. Thirty-six countries have an electricity crisis.

Cosgrove-Davies says it will need a 500 percent increase in investment over the next decade to meet sustainable development goal (SDG) seven, which calls on all countries to provide “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy”.

Yet Malawi, like most of sub-Saharan Africa, has huge natural resources, which if tapped should be able to provide electricity for all. Solar electricity could cover 50 percent of the country’s power needs in a short time, and hydropower could be greatly increased.

Light at the end of a tunnel

The best hope, say government ministers, is multilateral banks working with private investors.

The World Bank, Power Africa, the EU, the Shell Foundation, the UK government and the international Solar Alliance have agreed to help develop renewable energy across Malawi and other power-poor African countries.

Malawi has been told it could apply for $500 million.

Optimism is high. Connecting Malawi’s many thousands of villages to centrally produced power plants via a national grid used to be seen as the only option. Now it is seen to be unrealistic and too costly. Instead, renewable energy is becoming much cheaper and easier to install.

Micro-grids, which see whole villages being provided with solar or wind power, independent of the grid, offer another energy future. In Nambuma, people are not waiting for the grid to arrive, says Kamzitu.

Solar is now seen as the way forward. People want power, now. Only 50 households have generators, but over 200 families have installed solar. They see it as more reliable and it’s easy and cheap to charge up. And they don’t have power cuts.

SolarAid will continue to push for more mini-grids, more solar and other renewable sources of power. Whilst the majority of Malawian’s wait for these services we will continue to distribute pic solar lights to those most in need – if you can, please help by supporting out work.

An update from SunnyMoney Malawi

In December we worked closely with VSLs (Village Savings and Loans) to make lights available to their members. We ran a promotion of a reduced retail price for the month. This was very successful. Our top selling agent was Suzen Kalagho. She has been working with us for some years, but had previously been a small scale agent. She is a Village Agent for more than 15 VSL groups, with an estimated membership of 300. She is well connected and trusted within the community. Alongside her Territory Coordinator, Donnex Muva, she worked tirelessly in November and December, promoting the SM100 solar light, then visiting each group at the appropriate time, and making sales. Her total sales in November and December were 463, more than 1.5 times her membership base. She is now interested in progressing to become a super agent and start selling the Pilot X PAYG (Pay As You Go) solar light and phone charger. We will continue to support Suzen with financing and customer recruitment to address the countries power problems from the bottom up.

Brave Mhonie, General Manager, SunnyMoney/SolarAid Malawi

Formation of SunnyMoney Solar Sales Cooperatives

We have formed two cooperatives which are dedicated to selling solar lights in Balaka and Chikhwawa – both in the Southern Region of Malawi. The idea behind the cooperatives is to find local and self sustaining solutions to the challenges of capital financing for solar businesses. The groups formed so far are; Balaka SuperAgent Cooperative (SAC ) and Umodzi Cooperative in Chikhwawa. The Balaka SAC has 5 members who have invested in PAYG solar business. Among themselves, they raised a capital of MK 450,000.00 which was used for group loan request as shares at FINCOOP. In return, the group received a loan of MK 900,000.00 which was used to pay for 50 PAYG solar phone charging lights as start up capital. It is exciting to report that the group is doing very well and they have started loan repayment.

In Chikhwawa, the group decided to invest in SM100 solar lights before they jump to mid range, PAYG. The group has 20 members who are very influential and active in community development activities, each member will contribute MK 50,000.00 as start up capital which they will also deposit into FINCOOP group account to access the loan which will enable them to buy more products. So far, they have fully registered with FINCOOP and they are in the process of saving money for capital investment.

In Chikhwawa, the group decided to invest in SM100 solar lights before they jump to mid range, PAYG. The group has 20 members who are very influential and active in community development activities, each member will contribute MK 50,000.00 as start up capital which they will also deposit into FINCOOP group account to access the loan which will enable them to buy more products. So far, they have fully registered with FINCOOP and they are in the process of saving money for capital investment.

Brave Mhonie, General Manager, SunnyMoney/SolarAid Malawi

We are doing all we can to help Malawi but finances remain the main barrier – if you can, please help by supporting our work.